Ryder Cup 2025: How Europe’s team spirit defeated America’s individual stars

When Europe’s golfers celebrated another Ryder Cup victory on Sunday evening, the emotions were mixed.

Relief, certainly, after surviving a late American onslaught. Pride, too, in a performance that for two days bordered on flawless.

And perhaps, amid the champagne-soaked smiles, a familiar satisfaction: once again, in a contest defined by individuals, it was the stronger team that triumphed.

The scoreboard told the story: Europe 15, USA 13: a narrow margin, but one built on a platform of dominance.

From Friday morning through Saturday evening, Luke Donald’s European side overwhelmed their rivals.

They led 11.5-4.5 heading into the singles, a record advantage. The foursomes and fourballs showcased chemistry, trust, and tactical nous.

By the time the singles began, some pundits whispered about the possibility of a record-breaking rout.

Yet golf rarely follows a script. The United States, wounded but proud, clawed their way back on Sunday.

With six wins in 11 singles matches, and one halved between Harris English and Viktor Hovland after the Norwegian picked up an untimely injury, Keegan Bradley’s team reminded the world why they were pre-tournament favourites.

In the end, though, the hole they had dug over the opening two days was too deep.

Team Europe reclaimed the Ryder Cup, and in doing so, underlined a timeless truth in sport: a united team will so often outlast a collection of brilliant individuals.

Here, Sports News Blitz writer Ben Phillips looks into what led to this monumental European win and how a brilliant team can so often overcome a group of top individuals.

The anatomy of a European victory

On paper, the Americans looked fearsome. The world’s top 10 players stacked the line-up, and every member of Bradley’s squad was capable of winning on their own.

But the Ryder Cup is not stroke play; it is not about who can shoot 64 in calm conditions on a Thursday morning. It is about partnership, resilience and pressure.

Donald leaned heavily on proven pairings. Rory McIlroy and Shane Lowry embodied Irish grit and camaraderie, feeding off one another’s passion.

Jon Rahm and Tyrell Hatton provided a blend of power and precision.

Tommy Fleetwood and Justin Rose brought a level of composure and experience that very few could compete with.

This cohesion was absent from the Team USA camp. Pairings looked uncertain. Synergy was forced rather than natural.

Too often, American players seemed to compete alongside each other rather than with each other. In a format where “we” matters more than “me,” Europe exploited that gap ruthlessly.

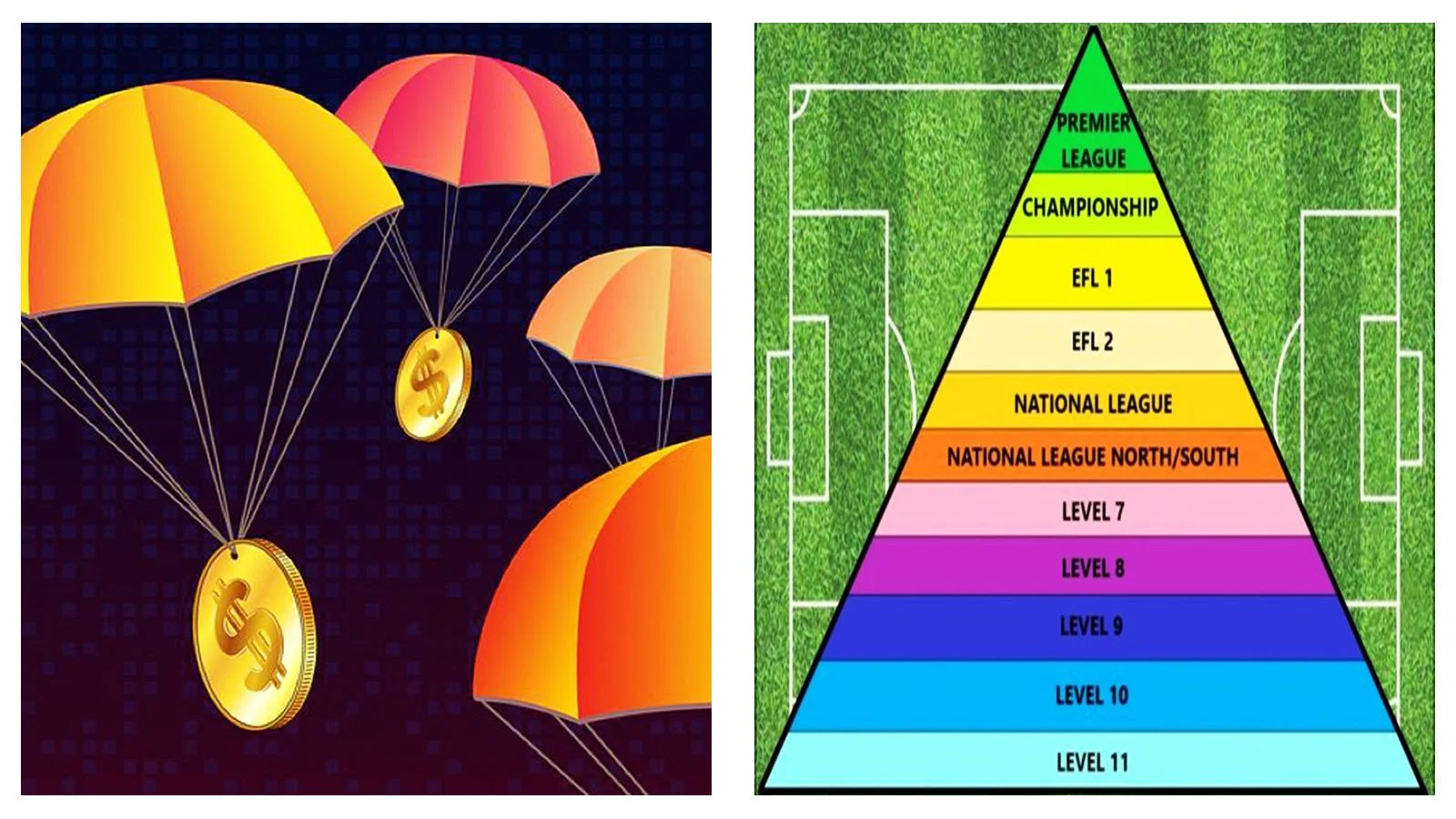

MORE BY BEN PHILLIPS: Soccer news: Are parachute payments damaging the fabric of English football?

Sunday’s near-turnaround

Of course, the United States’ Sunday rally cannot be dismissed.

Scottie Scheffler silenced critics with a gritty win. Xander Schauffele’s putter finally caught fire. Justin Thomas, written off by some earlier in the year, rediscovered his Ryder Cup magic.

Their fightback was spirited, their quality undeniable - but Ryder Cups are not decided solely on Sunday.

By then, the momentum is often set.

Europe’s cushion was built on chemistry in team play. For all America’s late surge, the script had already been written.

Lessons from other sports

The Ryder Cup’s recurring story - Europe, the collective outsmarting America, the individualistic - is hardly unique in sport. History is littered with examples where unity conquered raw talent.

Take Euro 2004. Greece, under Otto Rehhagel, stunned the continent.

They had no Zinedine Zidane, no Luís Figo, no teenage Cristiano Ronaldo. But they had shape, discipline and belief.

One by one, the giants fell, culminating in a final where the hosts, Portugal, blessed with flair players, were undone by a resolute, unshakeable Greek unit.

Or look at basketball. The 2004 Athens Olympics provided one of the sport’s great shocks.

The United States, boasting NBA stars like Allen Iverson, Tim Duncan and a young LeBron James, were expected to cruise.

Instead, they fell to Argentina in the semi-finals. Manu Ginóbili and his team-mates didn’t match the Americans for individual pedigree, but their understanding, ball movement, and clarity of roles proved decisive.

That Argentine team became immortalised not for individual brilliance, but for the triumph of togetherness.

Cricket offers a similar parable. In the 2019 World Cup, India and Australia fielded line-ups glittering with star batsmen and bowlers.

Yet it was England, built on balance and contributions from all corners of their XI, who lifted the trophy.

From Ben Stokes’ nerve to Jofra Archer’s calm under pressure, it was the collective that mattered most in the most dramatic final the sport has ever seen.

Rugby, too, is a theatre where teamwork outweighs individualism.

England’s 2003 World Cup win owed as much to collective grit and organisation as to Jonny Wilkinson’s golden boot.

When they beat Australia in Sydney, it wasn’t the Wallabies’ stars who shone brightest; it was England’s refusal to break shape, to deviate from the collective plan.

Each of these examples mirrors what unfolded at Bethpage in 2025: individuals may shine brightly, but sustained success requires the bonds of a team.

Why does Europe so often prevail?

The recurring question lingers: why does Europe, often the underdog in world rankings, so frequently beat the Americans?

Part of the answer lies in culture. For many Europeans, the Ryder Cup is the pinnacle.

National pride is amplified by the chance to unite under a continental flag. Players grow up watching Seve Ballesteros inspire, Ian Poulter roar, and José María Olazábal fight.

They inherit a tradition of unity that transcends personal accolades.

The United States, meanwhile, approaches the event differently. Their players live in a world dominated by the PGA Tour and majors, competitions that define legacies.

The Ryder Cup, while prestigious, does not occupy the same cultural space. For some, it is an interruption rather than an obsession.

Preparation plays a role, too. Europe has embraced analytics, psychology, and long-term planning.

Captains like Donald, Padraig Harrington, and Thomas Bjørn have invested in pairing science, personality management, and role definition.

By contrast, American captains sometimes appear reactive, adjusting on the fly rather than building continuity.

ALSO ON SNB: Lewis Hamilton says farewell to Roscoe: ‘The hardest decision of my life’

The human element

But beyond strategy and culture, there is something deeply human about Europe’s success.

The Ryder Cup strips golf of its individualistic armour. For 72 hours, players become team-mates, friends, brothers-in-arms. They are asked not to play for themselves but for one another.

Europe buys into that ethos more completely. Watch McIlroy hug Fleetwood after a crucial putt, or Rahm cheer as loudly for a partner’s birdie as for his own.

These are not hollow gestures; they are evidence of a genuine connection. In sport, emotion is fuel, and Europe seems to run on a richer supply of it.

What next?

The United States will lick their wounds, but they should take heart from their Sunday response.

Their players are too good, their talent pool too deep, for the tide never to turn. But if they are to reclaim Ryder Cup dominance, they must learn the lesson Europe keeps teaching them: partnerships win points, not résumés.

Europe, meanwhile, will savour another triumph built on togetherness. Their win in 2025 joins a long lineage of victories where spirit outshone stardom.

It is a story as old as sport itself, retold every two years in the Ryder Cup arena.

Conclusion

The Ryder Cup has always been more than golf. It is a mirror held up to sport’s greatest paradox: that games obsessed with individuals are so often decided by teams. Europe’s 15-13 win at Bethpage confirmed the pattern once more.

In years to come, fans may forget the exact scorelines or who won which singles match. But they will remember the broader lesson, that a group united by purpose can overcome even the most dazzling of stars.

Europe understood that truth. America, once again, did not. And that is why the Ryder Cup stays on this side of the Atlantic.

READ NEXT: Andrea Atzeni: ‘Giavellotto can be very competitive’ in Arc